You probably have heard the tongue in cheek expression “the bee’s knees”, meaning as good as you can get, a common saying that dates back to the “roaring” 1920s.

Some people might be wondering if real bees actually do have knees. The short answer is – kind of, and maybe more than you’d think. Bees don’t have knee bones. They do, however, have joints that function in the same way as knees. In fact, they have 30 of them.

What’s more the bee’s knees play a vital role in the production of honey.

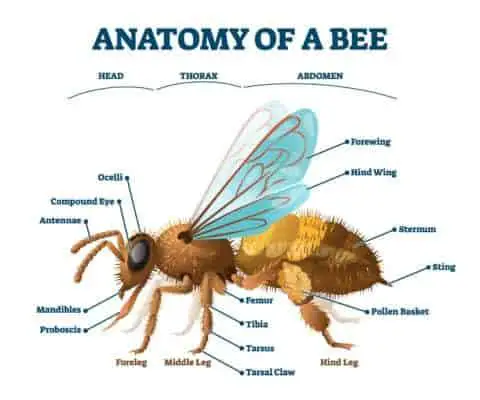

Basic bee anatomy

Currently, there are believed to be about 20,000 individual species of bee in the world. They range from the minute Euryglossina (Quasihesma) to the huge Megachile/Chalicodoma pluto.

Each of these species has its own unique anatomy. That said, the basic anatomy of the European Honeybee (Apis mellifera) can be used as a guideline to the basic anatomy of bees in general.

A bee’s body consists of a head, a thorax, and an abdomen. The head is the smallest part of the bee’s body and holds the eyes, proboscis, mandibles, and antennae. The thorax is larger than the head but smaller than the abdomen and it holds the bee’s two pairs of wings (forewings and hindwings) and its three pairs of legs.

A bee’s forelegs and middle legs are relatively straight and extend forwards so that the feet on these legs are near the bee’s head. Its hind legs have a clear bend in them so that the feet are near the base of the bee’s abdomen.

The abdomen is the largest part of the bee’s body. It contains vital organs such as the bee’s heart. In honeybees, the abdomen is also the location of the wax glands and the honey stomach.

The wax glands produce the wax used to make honeycomb. They only function for about 6 days and then wither away. The honey stomach is actually used to carry nectar, which is then used to make honey. This part of the honey bee’s anatomy is hardened to stop digestive fluids from entering it.

From the outside, however, all humans can see is the stinger, if a bee has one.

A Bee’s Legs

A bee’s legs all have the same basic structure. They are divided into six segments. These segments are connected by joints, which perform the same function as knees.

Starting at the bee’s body, these segments are the coxa, the trochanter, the femur, the tibia, the metatarsus, and the tarsus. At the end of each leg, a bee has a tarsal claw (or pretarsus) which functions as a foot griping onto vertical surfaces far more efficiently than a human foot.

The Forelegs And Middle Legs

A bee’s forelegs and middle legs are practically identical. The most noticeable difference between them is that a bee’s forelegs extend almost straight forwards towards its head.

Its middle legs, however, extend diagonally forwards so the bee’s foot ends up much further to the side. A less noticeable difference between the two pairs of legs is that a bee’s forelegs have little “brushes” on them. This is so that the buzzing bee can clean its antennae.

The Hind Legs

Although a bee’s hind legs have the same basic structure as its forelegs and middle legs, they look very different. The most obvious difference is that there is a very distinct bend between the femur and the tibia.

A Honeybee’s Hind Legs

A honeybee’s forelegs and middle legs are much the same as any other bee’s forelegs and middle legs. Its hind legs, however, are very different. This is because the honey bee makes honey. To make honey, it has to transport pollen from flowers to the hive. The honeybee’s hind legs do most of the work in this process.

Brushes, combs, and a rake

A honeybee’s hind legs are covered with stiff hairs which, under a microscope, look just like brushes, combs, and a rake. These are used to gather the pollen on the honeybee’s legs and transfer it into the auricle.

The auricle

The auricle is located in the joint between the tibia and the tarsus. This means that, basically, it’s part of the bee’s knees. As the bee flies, it bends and straightens its hind legs. Each time the bee bends its knee, the auricle crushes the pollen. When the pollen has become as compacted as possible, the bee transfers it to the pollen sacks.

The pollen sacks

The pollen sacks (also known as the pollen baskets) are exactly what they sound like. When they are full, they can easily be seen without a magnifying device.

How strong are a bee’s knees?

The reason full pollen sacks can be seen very easily is that they are very big compared to the overall size of the bee. For comparison, two full pollen sacks can account for almost a third of a honeybee’s total weight.

Thanks to the bee’s knees, however, (and the use of nectar as an additional binding agent) the pollen is firm enough to be a solid pellet. What’s more, the long hairs on the bee’s legs also help to hold the pellet firmly in place.

In fact, scientists have discovered that a pellet will stay attached to a bee’s body until it is subjected to a force that is almost 20 times stronger than the force a bee will typically undergo during its flight.

The Bee’s Wings Are Important As Well

Most of us will only see a bee’s wings at work when the bee is flying around collecting pollen or on its way back to the hive with full pollen sacks. Beekeepers and scientists, however, know just how much work a bee’s wings have to do once it gets back to the hive.

The bee’s wings have many uses in the hive and one of them is to make it possible for the bees to produce honey. Bees fan their wings over the nectar and pollen in the honeycomb. This encourages the liquid in the nectar to evaporate. As the liquid evaporates, the liquid in the honeycomb thickens and ultimately becomes honey.

The Wrap Up

Bees don’t have knee bones, but they do have joints between each of the six segments on each of their six legs. These joints perform much the same role as human knees.

This means that you could say bees have 30 knees. In the European honeybee, two of those knees play a vital role in collecting the pollen the bee needs to make honey.

Sources

https://www.honey.com/about-honey/how-honey-is-made

http://www.microbehunter.com/microscopy-forum/viewtopic.php?t=3422