Honey bees like all insects need oxygen to live. If you ask, most people could tell you that humans like most animals have lungs that breathe in air and put oxygen into our blood for our bodies to use. It is also well known that fish have gills that allow them to extract oxygen from the water. We know bees don’t have gills like fish but do they have lungs like humans? If not, how do bees breathe?

So do honey bees have lungs? No, bees don’t have lungs. Their respiratory system is called a tracheal respiratory system which extends through their whole body including air sacs located in the head, thorax, and abdomen. Breath enters a bee’s body via spiracles between the segments of their abdomen and through their thorax.

How Do Bees Breathe?

For most animals, the breath is drawn in by muscles expanding the rib cage thus allowing the lungs to draw in a breath through the mouth and/or nostrils. It is in the lungs where gas exchange occurs allowing oxygen to diffuse into the bloodstream and carbon dioxide to be expelled. The blood is pumped throughout their body allowing this process to occur in every cell of the body.

The blood has several additional roles like carrying food to cells, hydrating cells and providing passage for the immune system to defend the body against threats.

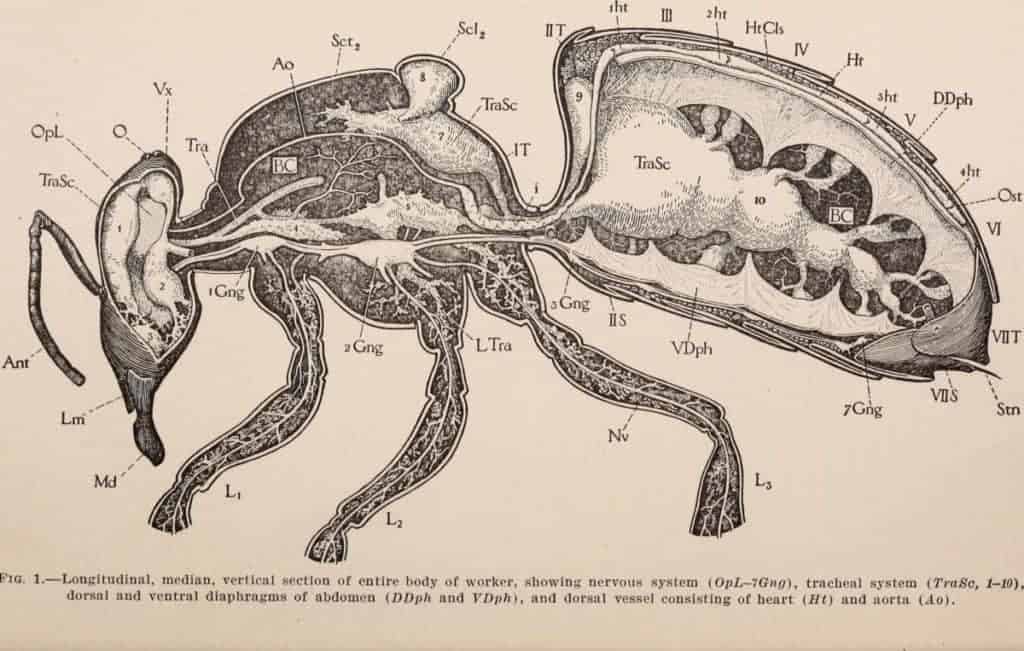

For bees, the burden of supply of oxygen and removal of carbon dioxide is not taken on by a bloodstream. It is taken care of by a system dedicated to the job. It is called the Tracheal System. The tracheal system is found in all insects. The way the tracheal system works is, in principle, the same. However, the layout of it can vary dramatically between different species of insects.

Anatomy Of A Bees Tracheal Respiratory System

There are three main parts:

- Spiracles

- Tracheal Sacs

- Tracheae and Tracheoles

1. Spiracles

Spiracles are the connection point through the bee’s cuticle or the wall of the bee’s body. The spiracle is a valve-type connection to a tube, the trachea that allows oxygenated air into the tracheal system facilitating the absorption of oxygen and also the expulsion of carbon dioxide.

The spiracles valve type function is closed and opened by contracting and releasing muscles that press against the wall of the bee’s abdomen and thorax. The spiracles can be closed if the bee finds themselves in water, effectively like holding their breath. Unfortunately, like humans, they can only survive submerged in water until the oxygen they have stored in their respiratory system is gone.

Some species of insects have up to twenty pairs of spiracles on their body. Honey bees have a total of ten pairs of spiracles. Three on the thorax, six on the abdomen, and one pair hiding away in the sting chamber. Honey bees don’t have any spiracles on their heads.

The first pair of spiracles located on the thorax is nestled in the hairs of the spiracle lobe. It is this pair of spiracles that is susceptible to the tracheal mite. The second pair are small spiracles, located just between and below the front and hind wings. The third pair of spiracles are largest and located on the sides of the thorax.

The abdominal spiracles pairs four to nine are located at the front of the plate sections (Tergites) of the abdomen. If you look closely at a honey bee you can see their abdomen pulsating movement of the abdominal sections is promoting airflow through the spiracles. The tenth pair is hidden away in the sting chamber.

Check out the short video of a nurse bee feeding larvae in a cell. You can see her abdomen sections pulsating, opening, and closing the spiracles.

2. Tracheal Sacs

Tracheal sacs are connected to a broad network of tracheae running throughout the honey bee’s body. The tracheal sacs are surrounded by fluid and unlike tracheae can expand and contract within the body of the bee. Changes in the pressure of the fluid surrounding the tracheal sacs are generated by the movement of the bees’ abdominal plate sections, this allows the tracheal sac to expand and contract.

The expansion and contraction of the tracheal sacs draws and expels air through the spiracles and pushes air through the tracheae network. As humans, we have only two lungs that draw and expel air from our bodies. However, this is where the similarities stop.

Honey bees have a lot more than two trachea sacs. In their heads, honey bees have three pairs of small tracheal sacs. There are no spiracles in the head of the honey bee so these tracheal sacs are connected via two large tracheae coming into the head through their necks.

In the head, there is one pair of tracheal sacs behind the compound eye and optic lobes of the brain. Another pair is located at the base of the mandibles. The third pair is behind the forehead under the antenna, sitting over the top of the brain.

The thoracic tracheal sacs hold the lowest volume of air of the three-body segments of the honey bee. In addition, two tracheal trunks extend under the spiracle lobe. These tracheal trunks not only supply the air for the tracheal sacs in the head they also connect to large tracheae that connect to the front legs and the main indirect flight muscles.

They also connect to the back of the thorax into a larger group of tracheal sacs connected to the second and third pair of spiracles on the thorax. This group consists of upper and lower pairs as well as a transverse sac in the scutellum. The lower pair connect to the back legs. Two large tracheae run through into the abdomen.

Two large tracheal sacs run down the sides of the abdomen tapering towards the back of the abdomen. The spiracles along the abdomen are connected to the tracheal sacs via broad tracheae. They also connect across the floor of their abdomen. In addition, there are a series of enlarged tracheae (almost small tracheal sacs) that branch off the large tracheal sacs towards the middle of the abdomen.

3. Tracheae And Tracheoles

Surrounding each tracheal sac is a network of tracheoles that allow oxygen to transfer from the tracheal sac to the tissue and vital organs of the bee’s body. This is in a way similar to the human body with arteries reducing to arterioles and finally down to tiny capillaries. The bees’ tracheae reduce down to tracheoles as they reach out to the tissues of the body and vital organs like the heart of the bee, which is engulfed by tracheoles.

Tracheoles will even penetrate high-energy muscles like the flight muscles where the cells demand a high level of oxygen. Tracheoles can be less than one micrometer in width and service tissues at a cellular level.

When the honey bee is less active the ends of the tracheoles will contain fluid. This is where the gas exchange will occur. Oxygen is absorbed and carbon dioxide is returned. As activity increases the fluid reduces and the gas exchange happens closer to the cells. In high-energy muscles like the flight muscles, when fatigue sets in the exchange of gases can happen right at the muscle cells themselves.

To understand fully why bees need such direct delivery of oxygen to their flight muscles, you need to have a look at how bees can fly and carry such heavy loads. We have an article the covers their flight in detail, How Do Bees Fly? They Are Heavy Lifting Marvels.

The Wrap Up

So do bees have lungs? Although bees have a series of little tracheal sacs that are a bit like mini lungs drawing in, storing, and releasing air they are however not lungs as we know them. So no lungs for bees, what they do have is a sophisticated and dedicated respiratory system.

Bees are built with amazing power to weight ratio. Bees can carry almost their body weight in pollen and nectar and their amazing respiratory system delivers all the oxygen it needs to carry that payload for miles at a time all day long.

Bees have some other parts of their anatomy that are truly amazing. We have written articles on them if you are interested:

Bee Antennae, An Amazing Sensory Super Highway

How do bees see the world? This is their superpower.

Sources

https://beeaware.org.au/archive-pest/tracheal-mite/#ad-image-0